Us, recycling and a celebration of 300 million years of British history.

The stunning limestone landscape of the Peak District’s ‘White Peak’ region lays at the very heart of the British Isles. These rocks were laid down 300 million years ago at a time when this part of the earth was close to the equator. The limestone, composing almost entirely from the accumulation of shells and calcerous skeletal remains of tiny organisms and sea creatures living in the warm shallow tropical seas of the time. Their fossils can be clearly seen in any piece of limestone.

Over millions of years these remains and the fluids trapped within them were buried deep in the earth by successive layers. The heat and immense pressure created by this process then forced any trapped fluids into the cracks and faults within the limestone where they cooled and formed crystals in layers of different minerals.

Over millions of more years, these rocks were uplifted once more, by processes deep within the earth. Ice ages came and went, and owing to erosion, the limestone was once more exposed at the surface.

Initially exploited during Roman times, these mineral veins contained lead and silver and were mined for these metals over subsequent centuries. Other minerals in these veins, such as Fluorspar, Calcite and Baryte were later mined for their chemical and commercial uses. A few mines are still operating to this day. However, at one certain location near Castleton in Derbyshire the Fluorspar occurred as a beautiful purple banded variety.

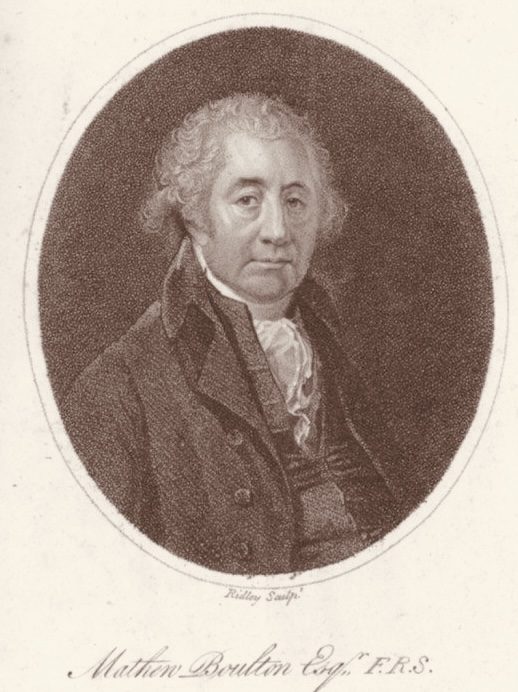

We don’t know exactly when it was first carved for its ornamental use. Undoubtedly, over thousands of years, humans passing over the area would have seen the coloured stone laying on the ground and in rocky outcroppings, perhaps taking a piece to be traded or worked. What we do know is that by the mid-18th century Blue-John and other coloured ‘spars and marbles’ from Derbyshire were being used by some of England’s most important architects, such as Robert Adam and Matthew Boulton, and represented the pinnacle of British design and craftsmanship whilst also highlighting and showcasing the natural treasures of the British Isles to the rest of the world.

Large ornaments, chimney pieces, clocks and such were commissioned for aristocracy and the wealthy. Blue-John was 18th century bling!

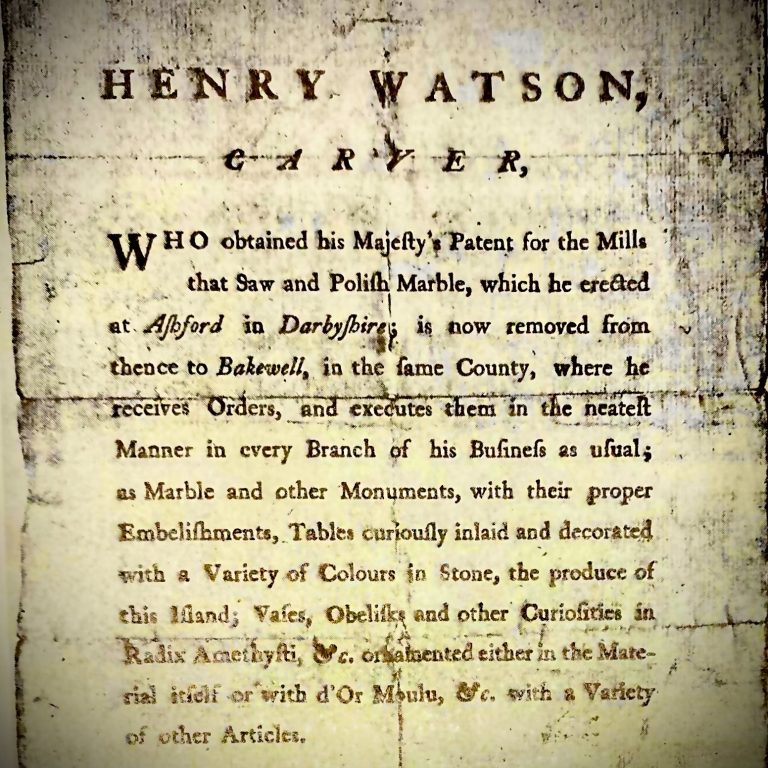

Henry Watson built a large, water powered marble sawing mill at Ashford in the Water in 1748. This was to service the surrounding stone carving industries that were becoming established and generally centred around Blue-John and “Black Marble“ working. The mill was still in use at the end of the 19th century.

By the early 1800’s, most of the towns and larger villages of Derbyshire’s white peak region had shops and ‘museums’ selling carved and worked ‘spars’ and ornaments, and many thousands of people were involved in the area from mining to carving. By the First World War the trade was in steady decline and new materials were more fashionable. By the mid 60’s only a dozen or so workers were still active. Today only Blue John Cavern, Treak Cliff Cavern and couple other small workshops are still producing and carving objects.

From the 18th century Blue John was treated with pine resin in order to make it workable. But from the mid-70s the stone was treated by some workshops by impregnating it with epoxy resin to harden it. Leaving only the Blue John Cavern and us still working in the traditional method of treating the stone with pine resin.

These minerals, these rocks, these materials, they are remnants of our past. The recycling of sea water and the creatures that once thrived within it. Wrought by the passing of unimaginable time and pressures into other forms. Presented to us by natural processes so that we my transform them once more to other forms.

©Copyright. All rights reserved.